There may not be a single live bee but the place is still abuzz.

An insect in an entomology collection may no longer be alive, but its presence, together with thousands of other deceased insects in institutions around the world, moves science forward.

The Academy of Natural Sciences, where I have worked for 6 years, houses approximately 4 million insect specimens and about 100,000 species. This is about 10% of the known insect species! The collection is managed by a group of curatorial staff and researchers and it is visited throughout the year by dozens of students and scientists from around the world.

The Academy of Natural Sciences Entomology Community (2017), the group includes a curator, collection manager, curatorial assistants, visiting scholars, visiting PhD students, undergraduate student interns, and volunteers. On either side of the group are cabinets that contain drawers upon drawers of insect research specimens.

The Collection

A leopard moth specimen two upward facing data labels and a barcode and unique identifying number, which is used for collection management. This specimen is about 100 years old, but it is in great shape.

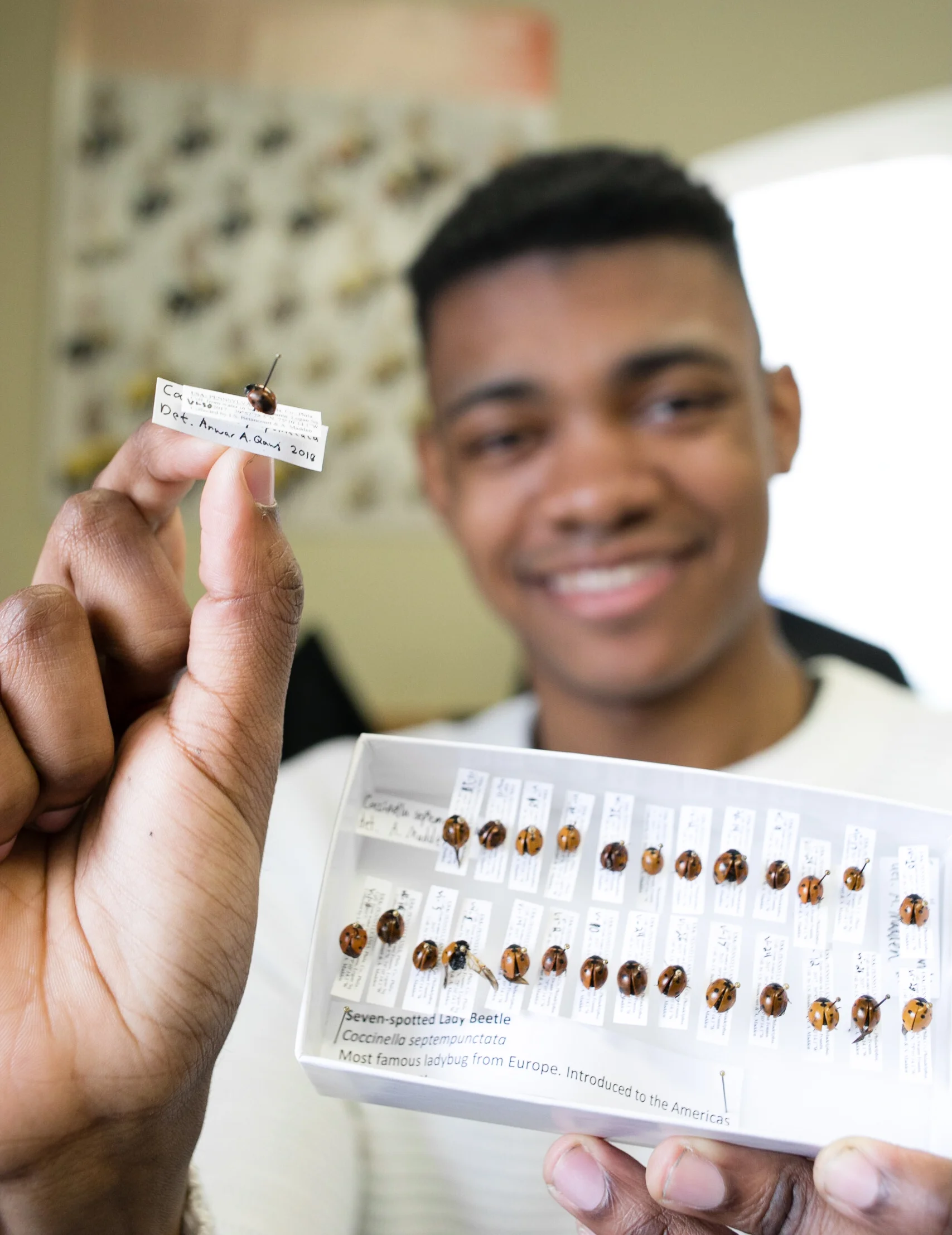

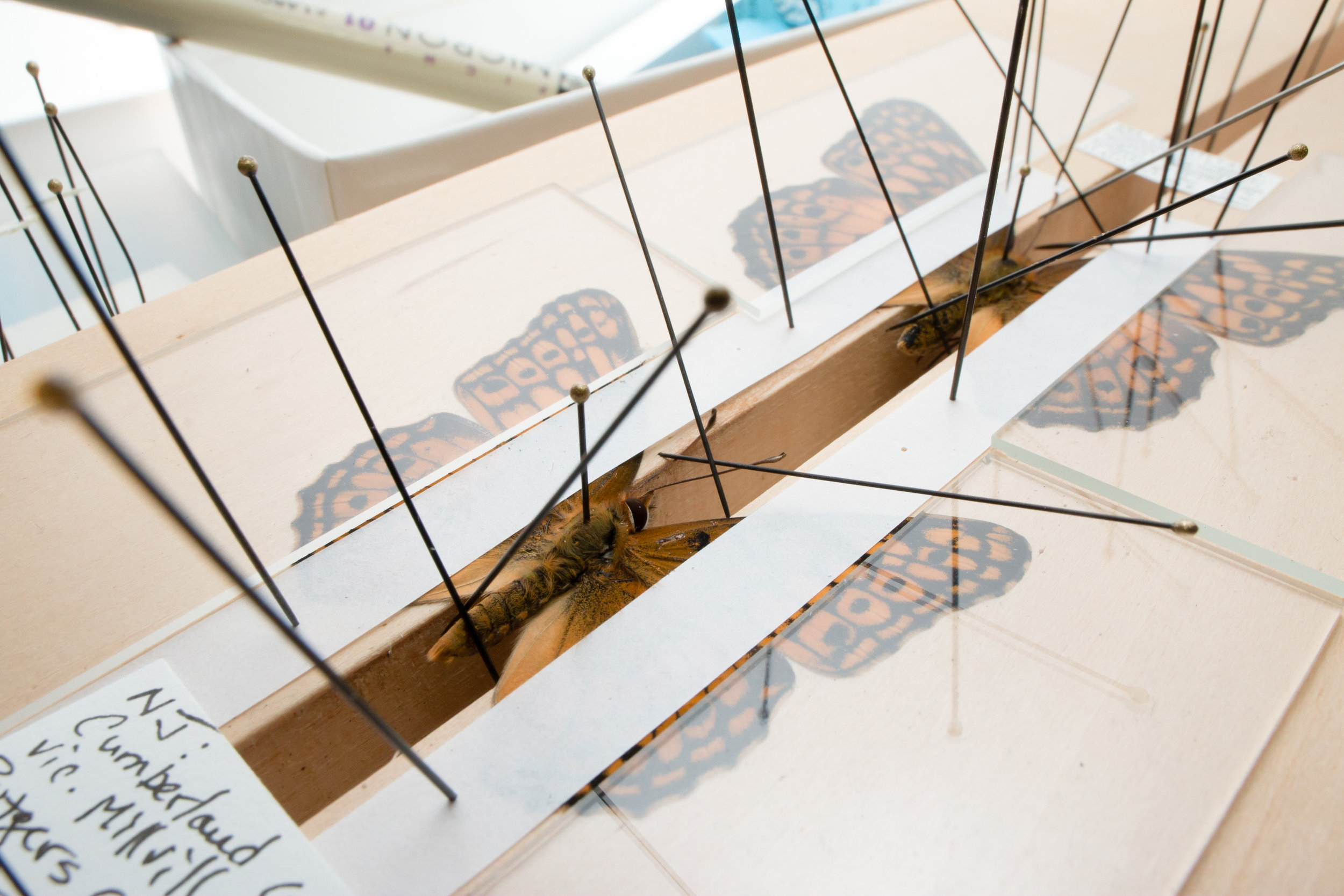

Insect specimens are preserved either in ethanol (if they are soft-bodied), on slides (if they are microscopic), in envelopes (if they are dragonflies), or pinned.

Since deceased, dried insects are brittle, the pin enables curatorial personnel and researchers to handle specimens without touching the insect itself, minimizing risk of damage. Labels with information about the specimen’s collection event are placed on the same pin as specimens.

In order for an insect to be research grade, it must be labeled with the date and location of the its collection event. With this data, scientists can keep track of changes in insect populations and learn about changes occurring on our earth.

Open a cabinet to find full columns of drawers of pinned insects. These particular drawers contain large grasshoppers.

Insect drawers are typically kept in large cabinets that roll back and forth on a track. It is a compactor system that allows maximal use of the space.

At left you can see collection manager at the University of Michigan, Erika Tucker opening a cabinet to access insects.

The lines on the ground are tracks for the cabinets. In the bottom right corner, are the handles used to roll the cabinets back and forth on the tracks. In this way researchers can switch the aisle and access a different row of cabinets.

These insect specimens look very similar; Both have raptorial front legs for catching prey. However, they are not closely related. The mantisfly, in the foreground, is in the scientific order, Neuroptera. The praying mantis, in the background, is in the scientific order, Mantodea. They are as related to each other as grasshoppers are related to butterflies. Having insect specimens available to compare with each other is critical for solving entomological problems.

The Community

Dr. Jon Gelhaus, Curator of the collection, examines crane fly specimens. He is a world expert on this insect group and has amassed over 10,000 crane flies at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Drawers upon drawers of moth and butterfly specimens are laid out on a large table and collectively researchers, curatorial personnel, and students come together to sort the material.

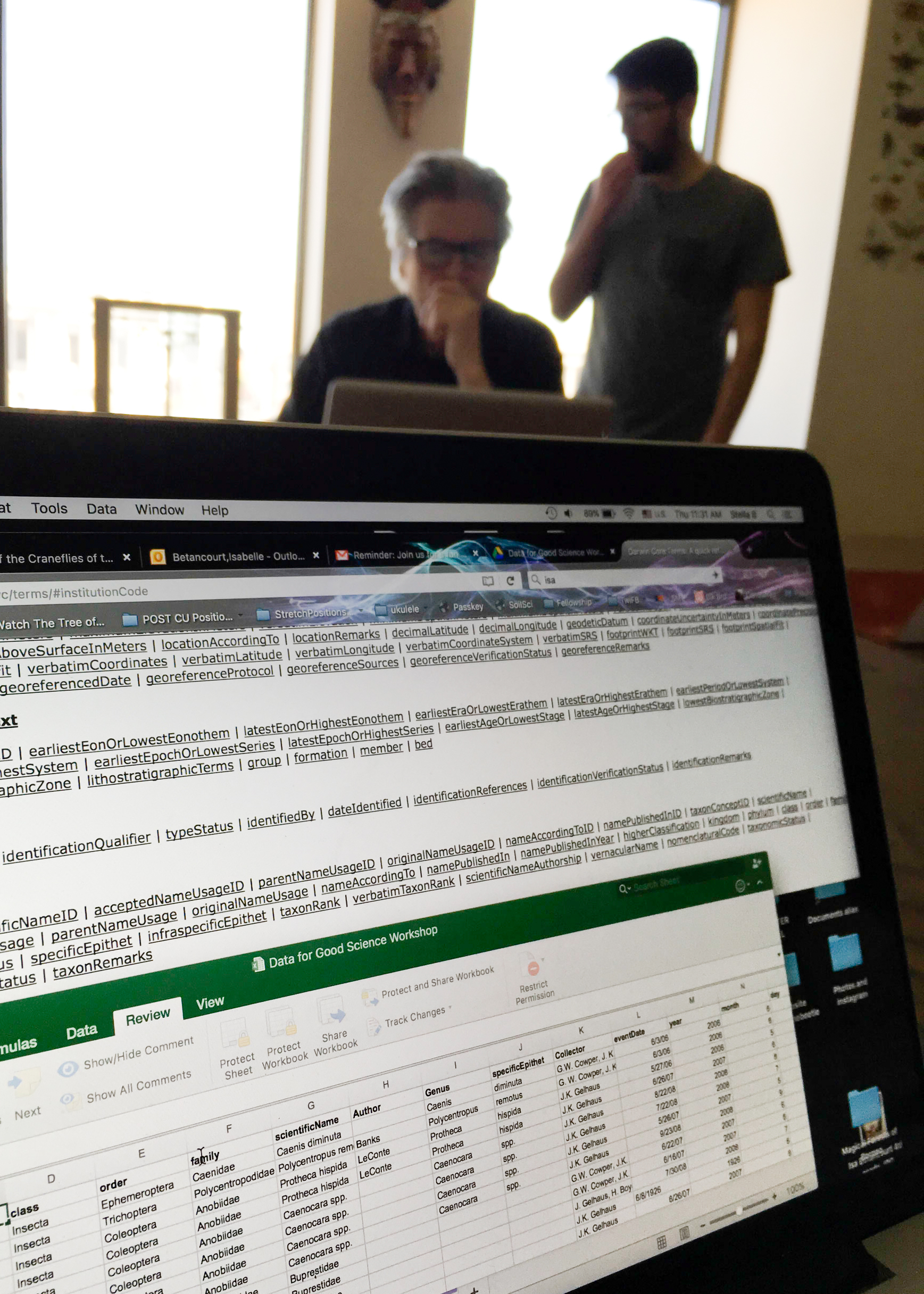

Curatorial staff are working to make digital versions of the physical insect specimens. This is a way to make the specimen data more accessible to science and big data projects. Digitization also helps with specimen management, making the process of fulfilling remote researcher’s requests for specimen data and images much faster.

PhD Student, Stephen C. Mason, Jr. brightens the office with his curated drawer of not insects, but jolly ranchers, which he offers to students and volunteers.